San Francisco set me to work.

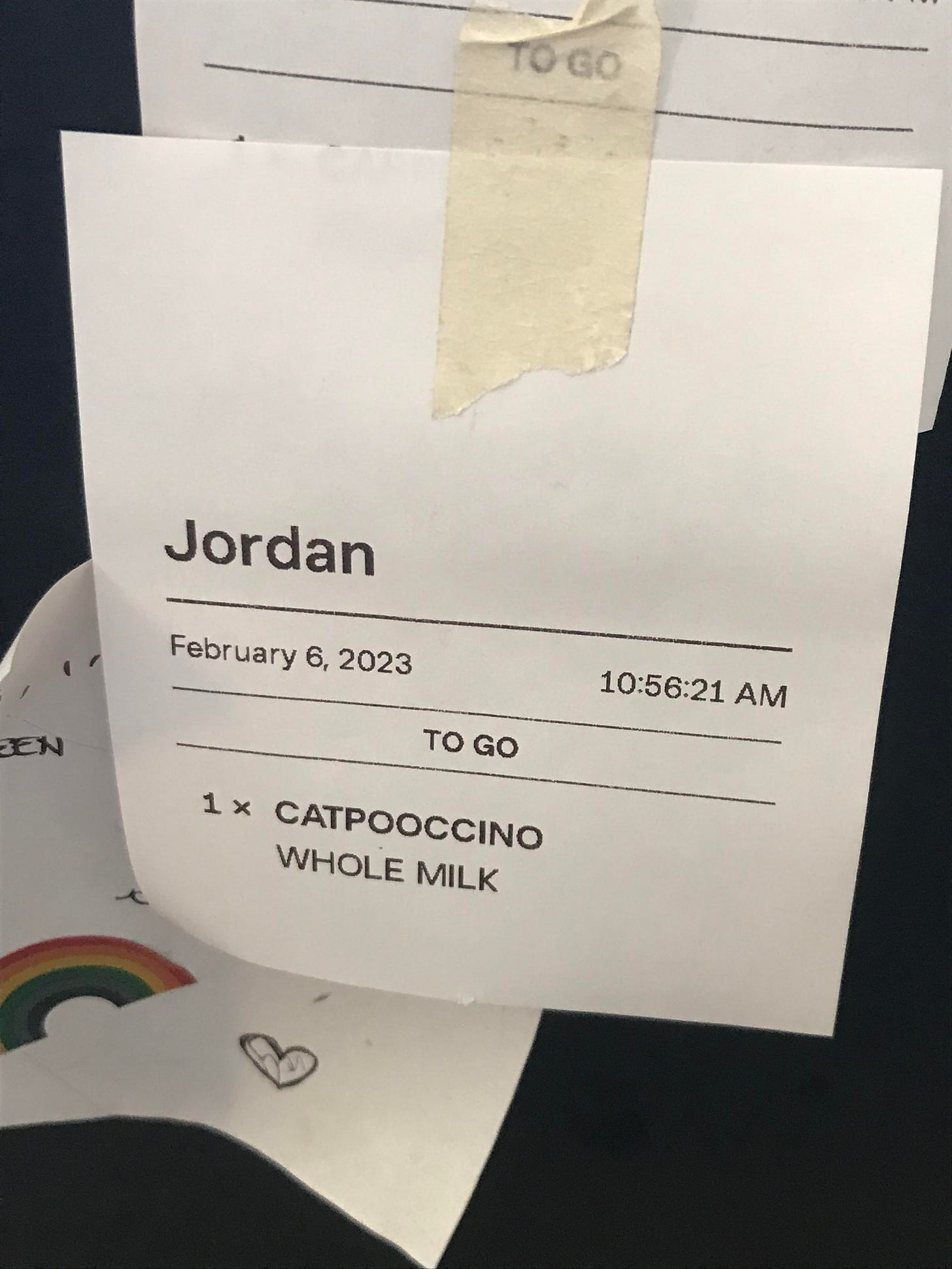

By the grace of a friend willing to lie about my experience, I slid into a barista job at a popular cafe, not really understanding what a cappuccino was but eager to apply my knack for utter acquiescence towards customers. It was not long before this job stripped me mercilessly of both of those naiveties. This cafe had been written into tourist handbooks in the early 2010s and had coasted on that reputation ever since, conjuring an evergreen influx of out-of-towners and travel influencers to add to the ensemble of Arcteryx-clad regulars.

It was, at times, ceaseless. Painful, of course, to watch a wrist heavy laden with this year’s Rolex Submariner deftly swipe passed the tip screen. To have to swat that same wrist away from someone else’s neon-green iced oat matcha from the bar while they growled, is this my cortado?

In time I came to hate them with all my heart, and I learned to be mean, curt, and aloof. The over-polite bisexual girl with a bob I had been pretending to be wilted away, died, making room for me to pretend instead to be an overworked, mischievous San Francisco lesbian. But beneath the psychic churn of new personas and cruel customers was the glorious routine of meniality. Their top-of-the-line Spirit espresso machine jutted into the seating area like the apron of a stage, and there’s nothing like house-made vanilla bean syrup and high grade caffeine to make you feel like a star.

In the spotlight of their eastward facing floor-length windows we performed an airtight routine with simple variations hundreds of times a shift. The repetition of this short regiment (grind, tamp, extract, steam, pour, serve, repeat) melted away the glamorous enchantment with specialty coffee I had hitherto suffered from, giving way instead to the real magic: the transmutation of raw material by exertive gestures, performed under the watchful eye of the spectating patron, into a revered and complete commodity form.

The equation was laid bare (at least, the part of the equation that happens in the coffee shop), as we weaved in and out of its terms and expressions bodily. Its rudimentary parts, as much as they attracted my fascination, were not the most vital revelation. What I really adored was the intuitive understanding that the choreography of my body, synced with a few pieces of machinery, could arrange assorted ingredients into a distinct object imbued with the effervescence of value.

Even on my walk to work, I felt that same spell all around me. The frames of the buildings I passed in a sleepy stupor pulsated with something extra metaphysical in the bleary glow of the crack-of-dawnlight. These, too, I thought, bulge with the history of the work that wrought them.

Instead of just reading Capital, I took daily pleasure in reinventing the wheel, in scrutinizing the residue, or imprint, that work had left on my surroundings, speculating that it must be responsible for the looming stature of the grove of Victorians I passed every day. I imagined that I could sense their culmination, the sum total of the repetitive gestures that had built them; the bend of the carpenter’s elbow and the pressure of their wrist on the circular saw; the arc of the house painter's brush stroke; the furtive touch of the homeowners fingers on the deadbolt; the angled neck of the scavenger, looking down each side yard by rote for recycling bins. Could you understand the world as a series of gestures — some implied, some displayed publicly — materialized?

I was feeling downright oracular at this point, having somehow arrived at Marx’s labor theory of value mostly via mid-20th century theatre textbooks. This was probably inevitable, since during my first few years in San Francisco my attention was split equally between work and a renewed desire to act. I practiced my lines underneath my KN95, spitting 1-and-a-half-minute dramatic monologues into the dish pit over and over again. On my ten minute breaks, I would sit in the middle of the cafe and read Constantin Stanislavsky and Michael Chekhov, obviously baiting people into asking me about it.

I became increasingly enamored with the latter, carrying his seminal work On The Technique of Acting with me everywhere I went like a cipher. Chekhov, too, was obsessed with repetitive motion. For him, movement, when performed enough times, could become a kind of container for feeling, or even a gateway to psychic depth. He called this practice, the psychological gesture. Rather than working oneself into an emotional fervor through (sometimes psychosis-inducing)1 mind games, he proposed that a gesture could be selected which represented an emotional state, and could be repeated so often that it eventually could be performed in the mind without moving the body at all to invoke the feeling it stood in for. Thus the interiority of the actor onstage, once a Freudian nightmare of sense memory and emotional triggers, would be replaced with a series of psychological gestures — in other words, imaginary choreography.

This body-first framework, while a departure from most acting styles of that era, was actually part of a lineage of movement practice that had bountifully proliferated in interwar Europe, and which has been enjoying a moment of sustained popularity recently as an amalgamation known as somatics. Part psychology, part bodywork, part movement practice, somatics has come into favor as a semi-formalized alternative to mainstream wellness.2 But the contents of somatics, sometimes marketed as a “liberatory embodied practice,” have just as often served the priorities of racial capital.3 Interest in the body as a site of knowledge production can easily be spun into interest in the body as simply a site of production.

Amongst others like Michael Chekhov, Rudolf Von Laban is credited as a foundational figure of modern somatic practice. He is perhaps best known for inventing a method of recording and annotating dance choreography, known as Labanotation. Lesser known is the fact that many of his early attempts to take down the moving body on paper were financed and proposed by industrial management professionals.

Some of Laban’s most enduring contributions to movement arts (specifically, his eight efforts, which are practiced worldwide as dance and acting exercises) were introduced in the book Effort; Economy of Human Movement, a squarely Taylorist attempt to divide up, label, and categorize the movements of industrial workers in order to maximize their productive energy on the factory floor.4

The revisionist introduction to the second edition of Effort paints their project as a contribution to the understanding of physical labor, towards the generous and philanthropic end of increasing the quality of life of the everyday working man. What Effort, same as all developments in the endlessly cruel field of scientific management, actually does, is create a new standard against which workers can be measured, disciplined, and replaced.

Since the origin of the current mode of production, the agents of capitalism have sought to conform the commodity of labor to a static and consistent shape. Labor is by nature variant, and often individual laborers are recalcitrant. The talkative worker, the clumsy worker, the worker who values quality over speed, the worker who takes pleasure in some tasks more than others, each of us in our own ways organically sabotage the fluid motion of capitalist extraction. As the labor historian and industrial pipe-fitter Harry Braverman so clearly put it: “in purchasing labor power that can do much, [the capitalist] is at the same time purchasing an undefined quality and quantity.”5

What is the suffering capitalist to do? In the case of management professional F.C. Lawrence, he turned to the arts, to Laban. But whether it was the work of artists like Laban and Frederic Alexander, or industrial psychologists like Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, all of the originators of so called time-and-motion-study sought to contain that amorphous force, the human body, until it became so consistent in performance that it could be maneuvered and replaced as easily as the machines it operated. This was the crusade of the movement of scientific management, made possible by investigations of the body that would later be adapted to sustain a human psyche ravaged by the immiseration of the conditions of work.

For a period of time, I practiced and taught the Michael Chekhov technique religiously, fascinated by its resonances and creative potential. But after years of daily practice and experimentation, the most good I seemed to be able to make of it was as a way to entertain myself through my grueling, repetitive, day job. The possibilities which had seemed endless in fact ended at the very edges of life under capitalism.

This was no coincidence. Movement art of this kind is no escape hatch, but part and parcel of the boundaries which have for hundreds of years encroached on the natural tendencies of life and land. That somatics can be applied as a therapeutic salve is not because of its immutable healing nature, but because prolonging the body's long era of servitude under capital has always been a part of the scheme. A machine part only continues to contribute value to the commodity as long as it remains in working condition.

In October 2023, I was pushed out of that coffee shop job because I demonstrated my support for Palestine, ripping down Zionist posters after my shift on my short walk back to my car. My abrupt departure was one of many such witch-hunts of service workers by owners terrified of being seen as having any opinion whatsoever on the genocide. It’s no fluke that Zionist sympathizers and their cronies perpetually come into conflict with the people who provide them with their daily services. In fact, Israeli settler-colonialism, the discipline of menial work, and the artists who arm bosses with technologies of surveillance and control, have been intertwined since the very beginning…

Michael Chekhov himself famously suffered a nervous breakdown from prolonged practice of Stanislavsky’s “Affective Memory” techniques. Biographers sometimes site this episode as the motivating event for the development of Chekhov’s own techniques.

Eddy, Martha H.. “A brief history of somatic practices and dance:historical development of the field of somatic education and its relationship to dance.” Journal of Dance & Somatic Practices 1 (2009): 5-27.

My point here is not that there is nothing emancipatory about somatic practice, but that there is nothing inherently emancipatory about it, and that its history and origins may engender it with the opposite tendency.

von Laban, Rudolf & Lawrence, F.C.. (1974) Effort; Economy of Human Movement. Macdonald & Evans, 2nd ed.

Braverman, H. (1974) Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. Vol. 26, Monthly Review Press, New York.